Executive Summary

- IRAs are individual investment accounts that can eliminate taxes on dividends and interest while also deferring income taxes or eliminating capital gains taxes.

- Understanding the unique characteristics of Roth and Traditional IRAs, and the math behind conversions, can create significant wealth.

- Advanced strategies, such as starting an IRA for your child or funding a “stealth IRA” can create incremental tax-free wealth.

The Individual Retirement Arrangement, or IRA, lacks the “horsepower” of the 401(k) that was discussed in the previous chapter. It features lower contribution limits and more onerous restrictions to be able to contribute at all.

But, if used correctly, the IRA is a tremendously flexible tool that can be strategically managed to lower your lifetime tax bill.

It is worthwhile to understand the different types of IRAs that Americans have access to, because the characteristics of each can create opportunities for “tax arbitrage” events throughout your life that can add up to significant incremental wealth.

Download This Guide As a PDF

Get the full PDF version of this Ultimate Guide To Tax Free Investing.

Your free instant download includes special bonus content.

The Value of Flexibility

When I was just starting off my career, I worked for a Chicago firm that did investment banking as well as valuations of privately held companies for estate planning purposes.

I did really well in that role. I received fast promotions, multiple raises, and generous bonuses.

A big reason for that was my willingness to take on any project. A managing director needed someone to make a last minute trip to a client in Iowa? Sign me up.

The CEO needed help with a slide deck for a presentation he was making to a business group the next day? I’m your man.

Need an extra body for the company basketball team’s game that tips off in 90 minutes? Put me in, coach.

I was young and single, without commitments to a family. That made me very flexible… which made me very valuable.

Flexibility is often underrated, in both employees and investments.

Overview of the IRA

Now let’s turn our attention to why the IRA is so valuable.

First of all, the IRA is a strategy that can be used in addition to – not instead of – a 401(k). For high earners looking to shelter significant amounts of their portfolios from taxes, that has obvious advantages.

Like the 401(k), an IRA is also a renewable tax incentive. As long as you have Earned Income, you can contribute to an IRA each year.

It’s also an individual account – that’s what the “I” in IRA stands for – which means that married couples can take advantage of this account twice each year.

The IRA also allows you to contribute at any point throughout the year – and in fact up until the tax filing deadline the following year.

I make IRA contributions for myself and my wife on January 1 of each year – a fun New Year’s tradition if you want to maximize the time your money has in a tax advantaged account.

But if you’re a procrastinator, you can make your IRA contribution when you file your tax returns the following April. Or you can spread contributions evenly throughout the course of the year.

The IRA is also flexible in that it can be both a source or destination of “rollovers.” Most commonly, this occurs when you leave a job that offered a 401(k). One of your options will be to “rollover” your 401(k) from your old employer into an IRA.

This can also go the other way; sometimes, you may want to “rollover” your IRA into a 401(k). Most IRAs will offer this option, which can create valuable flexibility.

The most valuable flexibility with the IRA comes in the form of the two “flavors” of IRAs that are available: Traditional and Roth.

The distinctions between Traditional and Roth IRAs – and the decisions around converting from the former to the latter – are a bit complicated. But they’re also incredibly important, so we’re going to dive deep into these concepts now.

Traditional vs. Roth

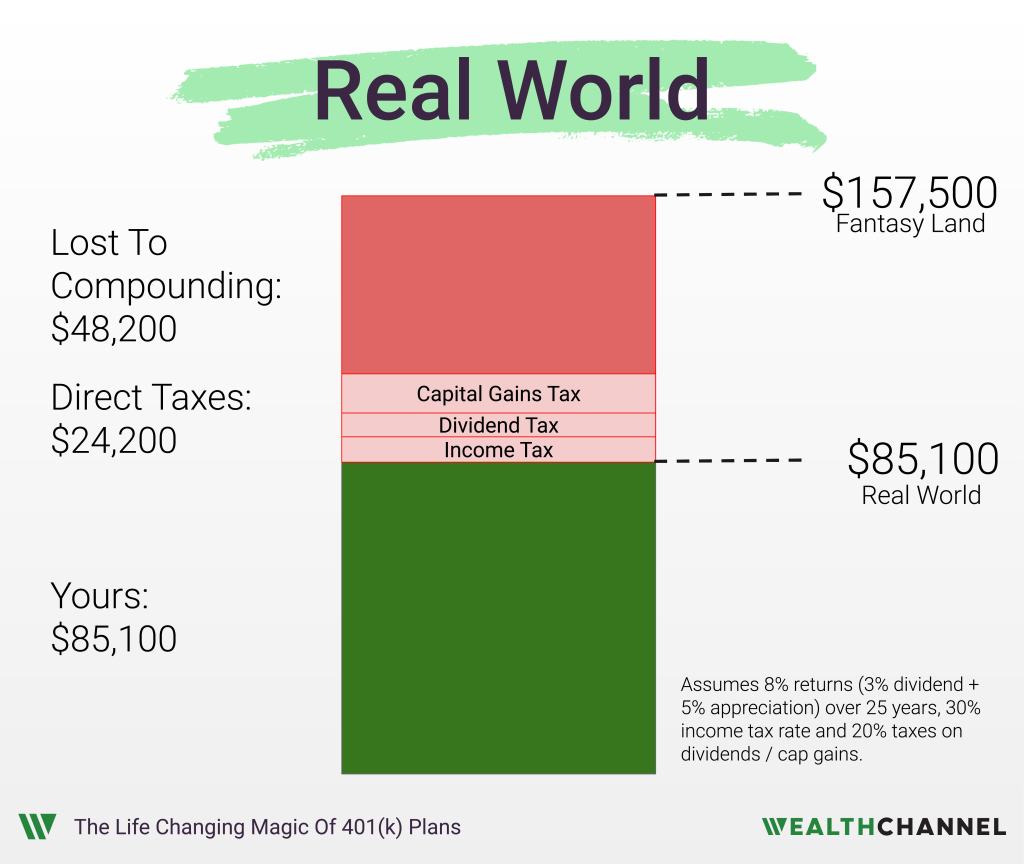

In the previous chapter, I explained the value of the 401(k) by comparing it to the alternative scenario, where your money is eroded by income taxes, dividend taxes, capital gains taxes, and the “compounding costs” that result from each of these.

You might remember this chart, where I highlighted the “steps back” that the 401(k) eliminates:

A Traditional IRA works in generally the same way as a 401(k). If you meet certain criteria (more on this in a moment), contributions to a Traditional IRA are tax-deductible. This is essentially the ability to contribute pre-tax dollars to a 401(k), in that it reduces your income tax liability in the current year.

The Traditional IRA also shelters your investments from taxes on dividends and interest, allowing you to reinvest all of these cash flows.

When you go to withdraw from a Traditional IRA, your withdrawals will be taxed as Ordinary Income. Again, this is why these accounts are described as “tax deferred.” You’ll still need to pay taxes eventually, but you’re able to kick that bill way down the road.

Roth IRAs

The Roth IRA has some similarities to the Traditional IRA, but some major differences as well.

The biggest difference relates to when income tax is paid. A Roth IRA is funded with after-tax dollars, which means that contributing to this account does not reduce your taxable income in the current year.

Once you get money into a Roth IRA, however, you’re done paying taxes… forever.

Like a Traditional IRA or 401(k), there are no taxes owed on dividends or interest.

Unlike a Traditional IRA or 401(k), however, there are no taxes owed when you withdraw from a Roth IRA.

The concept of Required Minimum Distributions, or RMDs, also doesn’t exist with Roth IRAs. You may recall that RMDs are a way for the government to force you to pay taxes starting at age 72. Since Roth IRA withdrawals are tax free, the IRS doesn’t care whether you make any withdrawals.

The ability to make tax-free withdrawals from a Roth IRA in retirement creates tremendous flexibility (there’s that word again!) that can be used to further reduce your lifetime tax liabilities.

Let’s return now to a table that compared the features of Traditional and Roth IRAs:

| Bucket | Examples | Tax Free Contributions | Tax Free Growth | Tax Free Withdrawals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxable | Brokerage Account | No | No | No |

| Tax Deferred | Traditional IRA, 401(k) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Tax Free | Roth IRA | No | Yes | Yes |

Traditional Vs. Roth Calculus

At this point, you hopefully understand the key differences between Traditional and Roth IRAs – in theory.

If so, you’re probably asking the obvious question: which one should I use – in reality?

The answer to that question has two levels. I’ll start by explaining which of the two types of IRA you should use… if you’re able to.

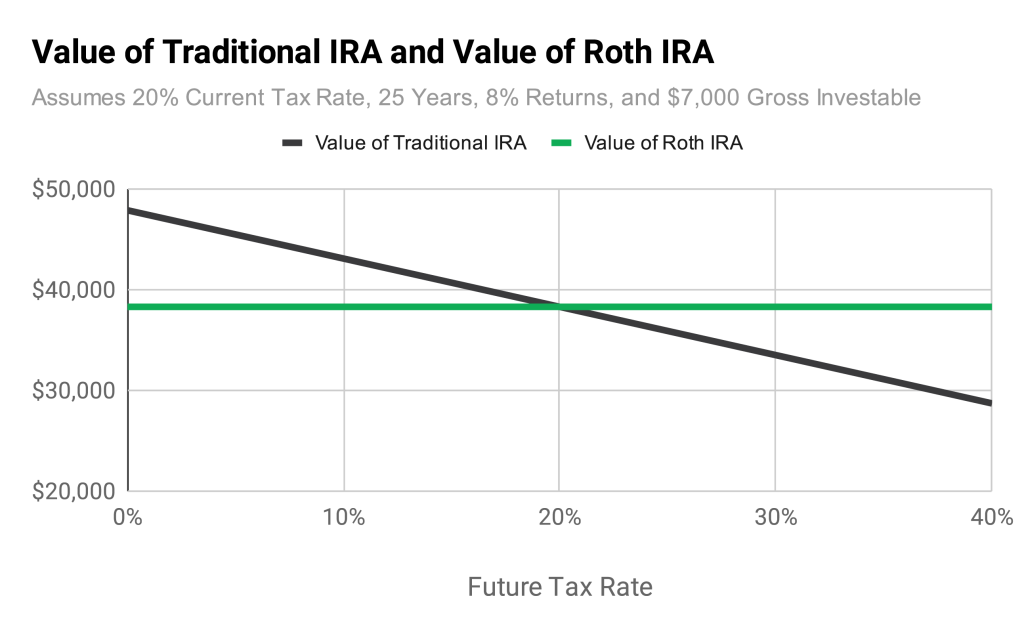

Let’s say that you received a $7,000 bonus from work, and want to save for retirement in an IRA.

Regardless of whether you invest in a Traditional or Roth IRA, your portfolio will return 8% a year for 25 years.

Currently, your marginal tax rate is 30%. In other words, your next dollar of income (or your next $7,000) will be taxed at a rate of 30%.

In retirement, you estimate that your marginal tax rate on Ordinary Income will be 20%. Of course, it’s difficult to predict what tax rates will be 25 years in the future. But this is your best guess.

Let’s consider two scenarios. In the first, you opt for the Traditional IRA. If you contribute your entire $7,000 bonus, this amount is tax deductible and you effectively defer all the taxes you would have otherwise owed on your bonus.

This $7,000 grows at 8% a year for 25 years (remember, the IRA shelters your investments from dividend and interest taxes) to $47,900. When you withdraw this amount, you’ll owe taxes at the 20% rate. That means $9,600 in taxes, and a net amount in retirement of $38,400.

The alternative is to go the Roth IRA route. Since a Roth IRA is funded with after tax dollars, you’ll first owe taxes on the $7,000 bonus. That leaves you with $4,900 to invest in your Roth IRA, which grows at 8% a year for 25 years to $33,600.

This entire amount can be withdrawn tax free.

In this case, you’re better off going with the Traditional IRA; using these assumptions, you’d end up with an extra $4,800 (the difference between $38,400 and $33,600).

Alternative Option

To illustrate the levers in this calculation, let’s assume that the tax rates are reversed: you’re taxed at a marginal rate of 20% today, but expect this to be 30% in the future.

In this scenario, using a Traditional IRA will leave you with $33,600 in retirement.

A Roth IRA results in $38,400 – a much better result.

This reversal illustrates the rule of thumb to follow with IRAs (and other tax strategies as well):

When given the choice, you generally want your taxable events to occur when your marginal tax rate is low and defer taxes when your marginal tax rate is high.

In the first scenario, you come out ahead by deferring taxes when your marginal rate is relatively high (30%) and having the taxable event – in this case, withdrawal from a Traditional IRA – occur when your marginal tax rate is relatively low (20%).

In the second scenario, you win by paying taxes up front (when your marginal rate of 20% is relatively low) and avoiding taxes later (when your marginal tax rate of 30% is relatively high).

That’s the framework for evaluating the Traditional vs. Roth decision, if you’re able to take full advantage of the benefits.

Unfortunately, that isn’t always the case…

IRA Eligibility

Unlike a 401(k), the IRA is subject to income eligibility restrictions.

Essentially, this means that taxpayers with incomes that exceed a certain level aren’t eligible to receive some of the tax benefits of IRAs.

In order to be able to contribute directly to a Roth IRA, here are the requirements for single taxpayers:

| Income (Single) | Roth Eligibility |

|---|---|

| Under $146,000 | Full $7,000 |

| $146,000 to $161,000 | Reduced |

| $161,000 or higher | Not Allowed |

The limitations for married couples filing jointly are:

| Income (MFJ) | Roth Eligibility |

|---|---|

| Under $230,000 | Full $7,000 |

| $230,000 to $240,000 | Reduced |

| $240,000 or higher | Not Allowed |

Believe it or not, the rules for being able to make a tax deductible contribution to a Traditional IRA are actually more complicated.

There’s one set of rules for single taxpayers who are covered by a retirement plan at work…

| Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) | Eligibility For Traditional IRA Deduction |

|---|---|

| Under $77,000 | Full $7,000 |

| $77,000 to $87,000 | Reduced |

| Above $87,000 | Not Allowed |

And another for those who are married, file jointly, and have access to a retirement plan such as a 401(k) at work…

| Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) | Eligibility For Traditional IRA Deduction |

|---|---|

| Under $123,000 | Full $7,000 |

| $123,000 to $143,000 | Reduced |

| Above $143,000 | Not Allowed |

Another set of rules for married filing jointly who don’t have access to a retirement at work — but with a spouse who does…

| Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) | Eligibility For Traditional IRA Deduction |

|---|---|

| Under $230,000 | Full $7,000 |

| $230,000 to $240,000 | Reduced |

| Above $240,000 | Not Allowed |

If you’re married and neither you nor your spouse have access to a retirement plan at work, there are no income restrictions.

We’re getting close to building the optimal IRA strategy. But there’s one more wrinkle that we need to cover first…

The Backdoor Roth IRA

If you’re over the income thresholds laid out in the tables above, you’re not completely out of luck.

There’s something called the Backdoor Roth IRA that, well, is exactly what it sounds like.

It’s a way for investors to effectively make a contribution to their Roth IRA, even if they’re over the income limit.

Here’s how it works…

First, the investor makes a nondeductible contribution to their Traditional IRA.

This is something that anyone can do, regardless of their income levels. The tables above showed the income thresholds that allow investors to make deductible, or pre-tax, contributions to a Traditional IRA.

But anyone can make nondeductible, or after-tax, contributions to a Traditional IRA.

As long as you have sufficient Earned Income. Essentially, you can only contribute to an IRA if you made money in the relevant year. More on this shortly when we discuss the Child IRA.

Immediately after making the nondeductible contribution to the Traditional IRA, the investor converts their Traditional IRA to a Roth IRA.

Practically, it may take a day or two for the contribution to “settle” and the investors to be able to make the conversion. This will vary depending on the platform you use.

As long as the investor has no other non-Roth IRA balances, this is a nontaxable event.

The end result is that your nondeductible, or after-tax, contribution to your Traditional IRA has ended up in your Roth IRA – without any taxes being paid. This investment can now grow tax free until you decide to withdraw it. That withdrawal, of course, will be tax free.

Pro Rata Rule

The Backdoor Roth IRA only works if you have no other non-Roth IRA balances. If you have a Traditional IRA that you have made pre-tax contributions to over the years, attempting a Backdoor Roth IRA will result in a tax bill.

In other words… in order to take advantage of the Backdoor Roth IRA, you need to get rid of your Traditional IRA.

Fortunately, the IRA is a very flexible vehicle, and there are two primary ways to accomplish this.

First, you can bite the bullet and convert your entire Traditional IRA to a Roth IRA. This will likely mean a tax bill today… but it may be a savvy long-term strategy.

The calculus here depends on your current and future tax rates. Hold that thought; we’re going to discuss Traditional-to-Roth IRA conversions shortly…

The second option is to roll your Traditional IRA into a 401(k). This is more of a workaround to the rules, but it’s a sound one.

You are able to zero out your Traditional IRA by moving the investments to a 401(k) that has identical tax advantages (and disadvantages).

The IRA Playbook

Now that we’ve covered the Traditional IRA, Roth IRA, and the Backdoor Roth IRA, hopefully you are feeling confident in your ability to determine the best option for you.

The flowchart below summarizes the process.

IRA Conversions

I started off this chapter explaining that the flexibility of IRAs makes them an incredibly powerful investment tool.

One great feature of IRAs is the ability to convert from Traditional to Roth at any point.

All else being equal, $1 in a Roth IRA is worth more to you than $1 in a Traditional IRA. The dollar in the Roth IRA will never be taxed again, whereas the dollar in the Traditional IRA will be taxed as Ordinary Income when you take it out.

Additionally, the Roth IRA offers greater flexibility because there are no RMDs – required minimum distributions – from a Roth IRA.

So, there’s value in moving money from a Roth IRA to a Traditional IRA. Unfortunately, there’s also a cost. A Traditional-to-Roth IRA conversion is a taxable event, and the amount that you convert is taxed as Ordinary Income.

Whether or not a Traditional-to-Roth IRA conversion makes sense depends on – you guessed it – your marginal tax rate.

If you’re in your peak earning years, you’re likely in a high marginal tax bracket. In these years, a Traditional-to-Roth IRA conversion likely won’t make sense since you’ll pay taxes on the converted amount at a high rate.

But there may be times where a Traditional-to-Roth IRA conversion is a great idea. If you’re taking a sabbatical, for example, you may have a couple years where your income drops.

When your income drops, your marginal tax rate generally drops. And when your marginal tax rate drops, the cost of a Traditional-to-Roth IRA conversion drops as well.

IRA Conversion Calculus

Much like the decision between a Traditional and Roth IRA at the time of contribution, the decision about whether or not to convert to Roth depends on your tax rates now and in the future.

While the equation is similar, it’s not quite identical. To understand why, let’s consider a hypothetical investor with $100,000 in a Traditional IRA.

This investor is contemplating a conversion to a Roth IRA. Let’s assume this conversion would be taxed at a 22% marginal rate, resulting in a tax liability due today of $22,000.

This tax bill would have to come from outside the IRA, since withdrawals aren’t allowed to cover this type of expense. So we’ll assume that this investor has $22,000 in his taxable account that he can use to cover the tax bill that would result from a conversion.

That means that the investor has to choose from two scenarios:

- In Scenario #1, he converts the $100,000 from Traditional to Roth and uses the $22,000 from his taxable account to pay the bill.

- The entire $100,000 remains in the Roth IRA, where it grows tax free and can be withdrawn tax free in retirements.

- In Scenario #2, he leaves the $100,000 in a Traditional IRA. That means he can leave the $22,000 in a taxable account, where it will grow at a “tax dragged” rate (since any dividend received will be taxed, lowering the reinvestment potential).

- The $100,000 stays in the Traditional IRA, where it grows tax free. Withdrawals from the Traditional IRA in retirement are taxed at ordinary income rates.

Let’s use the following assumptions:

- 8% annual return in a tax free account, split evenly between current yield and appreciation;

- 25 year time horizon;

- Current marginal tax rate of 22%;

- Expected marginal tax rate of 24% in retirement;

- Tax on long term capital gains and qualified dividends of 15%, both now and in retirement;

- 18.5% blended tax on distributions (an average of 22% tax on interest and 15% tax on dividends).

| Account | Value Today | Future After Tax Value |

|---|---|---|

| Roth IRA | $100,000 | $685,000 |

| Traditional IRA | $0 | $0 |

| Taxable Account | $0 | $0 |

| Total | $100,000 | $685,000 |

While in Scenario #2, you would have this:

| Account | Value Today | Future After Tax Value |

|---|---|---|

| Roth IRA | $0 | $0 |

| Traditional IRA | $100,000 | $520,000 |

| Taxable Account | $22,000 | $118,000 |

| Total | $122,000 | $638,000 |

In this scenario, you’re better off making the conversion today. This is because you anticipate having a higher marginal tax rate in the future.

The spreadsheet below provides more details on these calculations.

Dive into the data behind this example. Click here to open the underlying calculations in a Google Sheet. You can save as an Excel file or to your personal Google Drive.

It’s worth noting that Roth IRA conversions aren’t “all-or-nothing” events. If you have a $100,000 Traditional IRA, you can convert half of it to Roth. Or a quarter of it. Or just $10,000.

Again, there’s lots of flexibility.

Other Roth Conversion Considerations

Above, we walked through the calculations that you can make to determine if aTraditional-to-Roth IRA conversion makes sense.

In addition to this quantitative analysis, there are a few qualitative considerations that you should make.

First, keeping some assets in a Traditional IRA will give you greater flexibility in the future.

For example, you might unexpectedly have a low income year. Or Congress may unexpectedly lower tax rates.

Both of those would make you wish you’d waited to do the Traditional-to-Roth conversion.

Or Congress might go the other direction, and decide to eliminate the tax free withdrawal feature on Roth IRAs over a certain amount. Or they might increase tax rates, meaning that withdrawals from a Traditional IRA would be taxed at a higher rate.

Both of those scenarios would make you glad that you made a Roth conversion.

Ultimately, predicting the amount of tax free wealth created (or destroyed) by a Traditional-to-Roth IRA conversion involves both art and science. Yes, you can run the numbers and come up with a number and a recommendation.

But any such calculation involves making assumptions about values that are inherently unpredictable.

As the old saying goes: garbage in, garbage out.

HSA: The “Stealth” IRA

One of the most powerful retirement savings accounts is also one of the most overlooked.

Health Savings Accounts, or HSAs, are rarely used as tax advantaged investing vehicles.

But they are one of the only triple tax advantaged accounts available to most investors.

Here’s how an HSA works.

Investors who are on a High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP) can set up and fund a HSA. Contributions to the HSA are pre-tax, or tax deductible.

That means that making a contribution will reduce your tax liability this year, similar to a Traditional IRA or 401(k). That’s the first tax advantage.

Assets in an HSA can be invested in stocks, bonds, and other assets, and can grow tax free. In other words, there are no taxes owed on dividends, interest, or capital gains within the HSA.

That’s the second tax advantage.

Investors can withdraw from an HSA at any point to cover qualified healthcare expenses such as surgery, prescriptions, and a long list of other expenses.

As long as they’re to pay or reimburse for a qualified medical expense, these withdrawals from the HSA are tax free. This feature is similar to a Roth IRA. That’s the third tax advantage.

Most tax advantaged accounts are “either/or” in that they allow investors to either make tax deductible contributions up front or tax free withdrawals on the back end.

The HSA allows for both.

This can translate into significant wealth creation. Let’s return to our trusty framework: consider the alternative.

Specifically, let’s compare an investor who saves with an HSA versus one who uses a taxable account:

- Investor #1 puts $8,300 (the annual contribution limit for 2024) into an HSA.

- Because HSA contributions are tax deductible, this lowers his tax bill for this year by about $1,800 (assuming he’s in the 22% tax bracket).

- We’ll assume he invests this saved amount in a taxable account.

- Investor #2 puts $8,300 into a taxable account.

- This investor gets no tax savings for doing this.

Let’s use the following assumptions:

- 8% annual return in a tax free account, split evenly between current yield and appreciation;

- 25 year time horizon;

- Current marginal tax rate of 22%;

- Expected marginal tax rate of 24% in retirement;

- Tax on long term capital gains and qualified dividends of 15%, both now and in retirement;

- 18.5% blended tax on distributions (an average of 22% tax on interest and 15% tax on dividends).

| Scenario #1 | Scenario #2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Savings in HSA Today | $8,300 | $0 |

| Future After-Tax Value of HSA | $57,000 | $0 |

| Savings in Taxable Account Today | $1,800 | $8,300 |

| Future (After-Tax) Value of Taxable Account | $10,000 | $45,000 |

| Total Future After Tax Value | $67,000 | $45,000 |

Using the HSA to save for health care expenses in retirement creates about $22,000 of incremental wealth.

It is worth noting that the HSA is a renewable incentive, which means that investors can contribute to it each year.

The "Stealth" IRA

Now, you may be wondering how the HSA could possibly be used for retirement savings if one of the requirements is that withdrawals be used for qualified medical expenses.

If you withdraw from an HSA for a non-medical expense before you turn 65, you’ll owe both taxes and penalty on the withdrawn amount.

But once you hit 65, the penalty goes away. At that point, you can take money out of the HSA for non-medical expenses and only owe taxes on the withdrawal.

That eliminates one third of the triple tax advantaged status, and effectively turns the HSA into a Traditional IRA where investors receive a tax deduction up front and tax free growth for the life of the investment, but owe taxes on the back end.

There are a couple of minor differences. Investors will need to wait until age 65 to withdraw from an HSA penalty-free for a non-medical expense, whereas IRA withdrawals can begin at age 59 ½. But HSAs don’t have Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) of IRAs, providing investors with more flexibility in retirement.

The table below adds a third column on the far right, illustrating the outcome for an investor who funds an HSA and ends up withdrawing for non-medical expense in retirement:

| Scenario #1 HSA for Medical Expenses | Scenario #2 No HSA | Scenario #3 Stealth IRA |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Savings in HSA Today | $8,300 | $0 | $8,300 |

| Future After-Tax Value of HSA | $57,000 | $0 | $43,000 |

| Savings in Taxable Account Today | $1,800 | $8,300 | $1,800 |

| Future (After-Tax) Value of Taxable Account | $10,000 | $45,000 | $10,000 |

| Total Future After Tax Value | $67,000 | $45,000 | $53,000 |

This investor still comes out quite a bit ahead of the suboptimal alternative – investing through a taxable account.

Here’s how you should think about the HSA: best case, you get access to an account with triple tax advantaged status that you can’t find in a 401(k) or an IRA.

If you have to withdraw for non-medical expenses in retirement, you end up with (effectively) another Traditional IRA.

Note that a HSA isn’t all or nothing: many investors will end up withdrawing for both medical and non-medical expenses.

The spreadsheet below includes details behind these calculations:

Dive into the data behind this example. Click here to open the underlying calculations in a Google Sheet. You can save as an Excel file or to your personal Google Drive.

HSA Eligibility And Requirements

Unfortunately, the HSA isn’t available to everyone. It’s limited to those who are on a High Deductible Health Plan, or HDHP.

As the name suggests, HDHPs are plans that typically have lower premiums and higher deductibles. In 2024, HDHPs must have a deductible of at least $1,600 for individual plans and $3,200 for family plans. Those amounts are indexed to inflation, so they may increase each year.

Depending on your individual circumstances, the tax savings potential of an HSA may or may not be worth the move from a lower deductible plan to an HDHP. You’ll need to take into account your expected medical needs when making that decision.

The Child IRA

One of the best wealth creation moves you can possibly make is to start and fund an IRA for your children.

Perhaps no strategy better illustrates the Two Laws of Investing that we covered back in Chapter Two.

In case you forgot, those two laws are:

Law #1: The two best times to pay taxes are: later, and never.

Law #2: Compound returns are the eighth wonder of the world.

Let’s walk through what a Child IRA might look like. Suppose that you’re able to contribute $7,000 to a Roth IRA in the name of your daughter on her 5th birthday.

If the investment returns 8% a year, it will balloon to about $482,000 by the time your daughter reaches age 60.

Because withdrawals from a Roth IRA are tax free, your daughter would be able to use this entire amount to fund her retirement.

When setting up a Roth IRA for a child, you will almost always want to make a Roth contribution. Remember, a Roth IRA makes sense when your marginal tax rate today is lower than your expected marginal tax rate in retirement.

Many children will fall into the 0% tax bracket, meaning that their tax rate in retirement will certainly be higher than it is today.

Because of the 0% marginal tax rate, there is effectively no benefit of making a Traditional IRA contribution.

There are a couple of other reasons to love the Child IRA.

Setting up a Roth IRA is a great way to teach your kids about money. You can explain what the Roth IRA is invested in, watch the ups and downs of the portfolio, and impact some basics of financial literacy at an early age.

Second, the Child Roth is a great way to pass on wealth to the next generation without worrying about the potential negative consequences of a child inheriting a large amount at a young age.

Remember, withdrawals from a Roth IRA can’t start until age 59 ½. So you don’t have to worry about the silly things that an immature 18-year-old can do with a trust fund; by the time they access this money, they’ll be at or near retirement themselves.

The Challenge: Earned Income

Hearing about the incredible potential of a Child IRA, you might be asking: what’s the catch.

It’s a good question; unfortunately, there’s a big one.

For a child, the maximum IRA contribution is limited to the lesser of $7,000 or their Earned Income for the year.

What that means, effectively, is that your kid needs (legitimately) to make money in order to contribute to a Roth IRA.

Most young kids don’t have a viable source of income, unless they’re acting or modeling. So contributing to a Child IRA in the very early years will be difficult or impossible for most investors.

But once they start earning money from mowing lawns, babysitting, or other odd jobs, this door is opened.

And the Two Laws of Investing are still working in your favor. Even $1,000 invested at age 10 and returning 8% a year will grow to about $47,000 by age 60.

If a summer of bagging groceries at age 14 allows her to contribute the full $7,000, that would grow to nearly $241,000 by age 60.

If you or your spouse owns a business, you may have increased flexibility in generating Earned Income for your children and enabling Roth IRA contributions. You can hire your kids to work for your business at an early age, as long as you’re paying them a reasonable rate for the work that they’re doing.

This has the added benefit of reducing the taxable income from your business, effectively allowing you to capture the best features of both the Traditional and Roth IRA.

Setting up a Child IRA is fairly straightforward, and can be done for free with Vanguard or Fidelity. There’s no special account type; you are just opening an IRA for the benefit of a minor.

Again, the hard piece of this strategy is generating the Earned Income that will make the IRA contributions legal.

Important Note: Your child doesn’t have to directly contribute the money she earns; she just needs the Earned Income. In other words, she can spend the $1,000 she made mowing lawns on baseball cards and you can still contribute $1,000 to her Roth IRA.

It’s also important to note that generating Earned Income for a child typically creates a tax liability. Even if they are effectively in the 0% tax bracket (i.e., their income is less than the Standard Deduction), they will still have to pay FICA taxes to fund Social Security and Medicare.

You can refresh yourself about how these taxes work in chapter 2, and watch the following video to see how this works in practical terms.

The spreadsheet below includes the bath behind the numbers in this video:

Dive into the data behind this example. Click here to open the underlying calculations in a Google Sheet. You can save as an Excel file or to your personal Google Drive.

Three More Quick Notes...

This chapter has so far focused on the basic IRA strategies that are going to be relevant to most investors. Below are quick summaries of additional details about the IRA.

Self Directed IRAs

For most investors, an IRA from a “big box” provider such as Vanguard or Fidelity will be sufficient. These accounts are cheap and easy to set up.

The only drawback is that they are limited in what asset classes they can hold. You’ll have the ability to invest in a wide range of mutual funds, ETFs, and stocks. But most “alternative” asset classes will be inaccessible. This includes precious metals such as gold, cryptocurrencies, and many real estate.

If you’d like to invest in alternatives within your IRA, you’ll need to set up a self-directed IRA (SDIRA). These are pretty easy to set up, but will be a bit more expensive than a “big box” IRA from Vanguard or another low cost provider.

Multiple IRAs

There’s no limit on the number of IRAs that you can hold. So if you’d like to set up a SDIRA to invest in alternatives, it need not be your “primary” IRA.

In other words, you can set up an IRA with Vanguard that invests in “plain vanilla” asset classes such as stocks and bonds. And you can set up another IRA with a SDIRA platform to invest in alternatives.

SEP and SIMPLE IRAs

We’ve focused on the two primary “flavors” of IRA so far: Traditional and Roth. For business owners, however, there are some additional options including SEP and SIMPLE IRAs.

These can be powerful tools, but will only be applicable to a very small number of investors.

Bringing It All Together

We’ve covered a ton of material so far.

Let’s bring it all together now, and show the “hierarchy” of retirement savings that will makes sense for most investors:

| Priority | Account/Strategy | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 401(k), up to Employer Match | Until you reach your match limit, this is free money |

| 2 | HSA (if eligible) | Potentially triple-tax advantaged |

| 3 | IRA | Generally greater flexibility and lower costs than 401(k) Roth vs. Traditional decision depends on your current and future tax rates |

| 4 | Spousal IRA | Same as above |

| 5 | 401(k), to deduction limit | Lowers taxable income today, and shields assets from dividend and interest tax |

| 6 | Nondeductible 401(k) contributions (if available) | Shields assets from dividend and interest tax; may be eligible for Mega Backdoor Roth |

| 7 | Taxable account | No tax advantages, but no withdrawal penalties either |

The obvious caveats apply here: investing is highly personalized, and the exact prioritization will depend on your individual circumstances.

But hopefully you are now armed with an understanding of the different costs and benefits, and able to do much of that assessment.

Download This Guide As a PDF

Get the full PDF version of this Ultimate Guide To Tax Free Investing.

Your free instant download includes special bonus content.

Table of Contents

This page is part of our Ultimate Guide To Tax Efficient Investing. Follow the links below to read through the entire guide. Or, click here to download the full PDF version.

- Chapter 1: Why Taxes Matter (The One Big Myth) — The impact of taxes on your portfolio.

- Chapter 2: The Four (Yes, Four) Types Of Income Taxes — Understanding the “default” tax treatment your income receives.

- Chapter 3: Guiding Principles (And An “Aha Moment”) — Six rules of thumb that will make your life easier.

- Chapter 4: The 401(k) (Your Tax Free “Workhorse”) — My the 401(k) is the most powerful wealth creation account for most investors.

- Chapter 5: IRA Strategy (And the Value of Flexibility) — How to use IRAs optimally to minimize your lifetime tax liability.

- Chapter 6: Asset Location (And the Greatest Investment Ever Made) — Why it matters where you hold your bonds.